Thiago Fernandes:

Journey Through the World

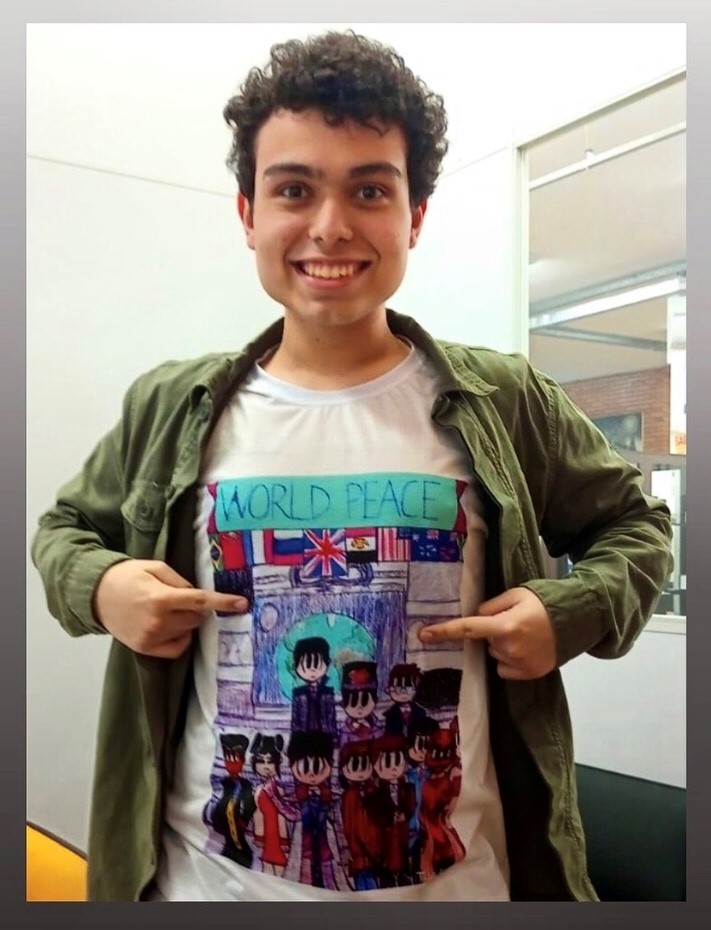

This exhibit was made possible by the collaboration and friendship of Veronica Federiconi, Autism Services CEO 2002-2023, with Kássia and Thiago Fernandes.

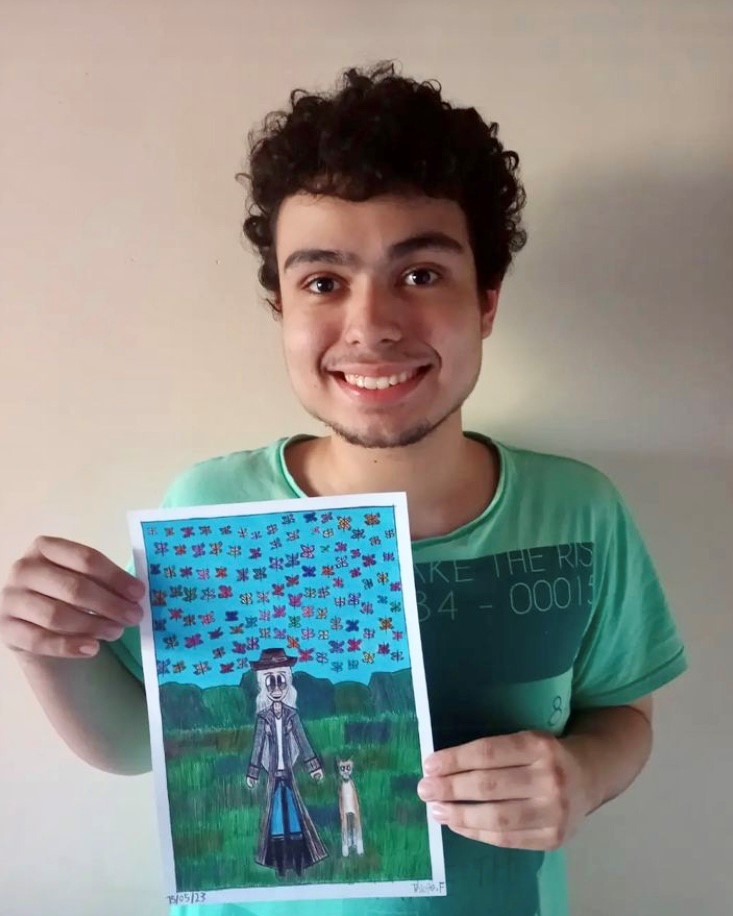

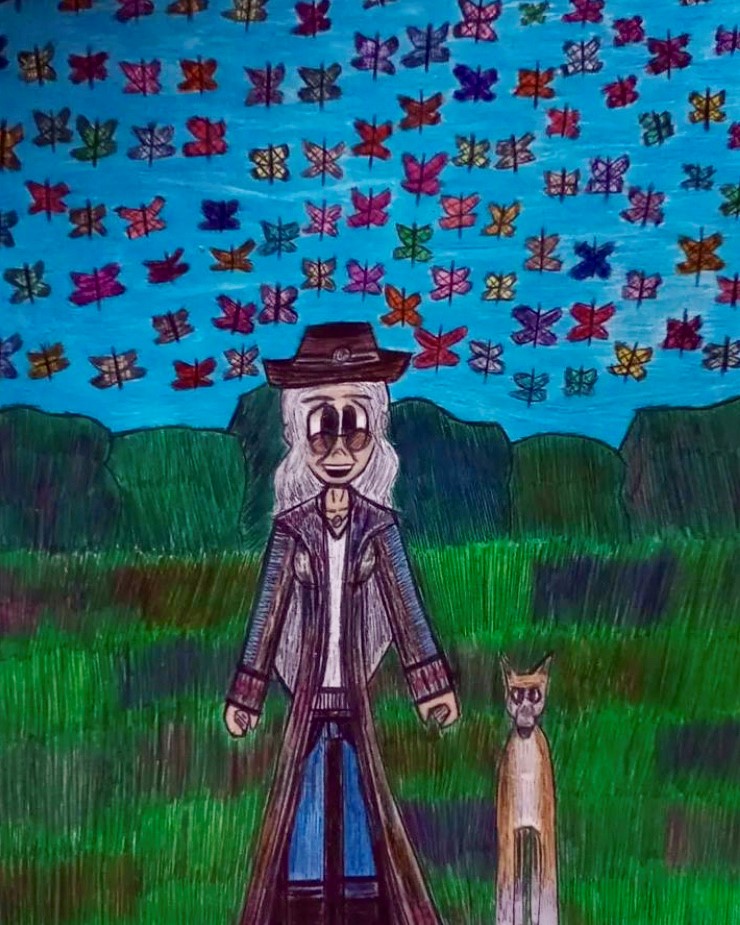

“This is a drawing of my good friend Veronica Federiconi with her dog, on a morning with a sky full of butterflies. Veronica you live in our hearts.” ~Thiago

“Thiago, your drawing brings so much joy to my heart. Please always know how honored I am to have you and your mom in my life. I love you both very much.” ~Veronica

THIAGO SANTOS FERNANDES is a Brazilian artist born in 2004 in Recife, Pernambuco. Thiago’s work has been exhibited locally and internationally, in person, and online, and has received awards in international competitions. Interested in the art of drawing since childhood, Thiago is autistic and expresses his emotions through his artwork. Early subjects were animated characters inspired by games and series, YouTubers, people he lives with, teachers, and artistic and political personalities. Currently, science fiction features prominently in Thiago’s work, including time travel and aliens. His particular focus is on countries of the world. He creates characters from various real-life nations and independently researches flags, tourist attractions, history, and other aspects of these locations about which he is curious. His preferred media are colored pencils and black and white pens on heavy-weight drawing paper (Canson 180 or 200 g/m2). Thiago occasionally experiments with new materials and techniques, most recently pastel, watercolor, and digital art. Presently he is developing two bodies of work featuring countries – mainly those less publicized by the media, and all 50 US states.

Exhibition Statement

“Journey Through the World” comprises drawings about people, forces, conflict, and peace, with accompanying descriptions provided by the artist. Forces around the globe are personified by subjects set against colorfully intricate land- and cityscapes. As in all Thiago’s work, garments and architecture celebrate the pageantry and traditions of their respective regions, with a futuristic flavor and anime-inspired stylization.

In two drawings of conflict, Thiago’s interest in sci-fi themes is on full display, as forces for good protect international locales against alien invasions. Imaginatively detailed characters and narratives abound in these vibrant compositions, meticulously rendered in a rich palette of hues.

When the drawings are viewed together in context with “Journey Through the World,” “There is Hope,” and “World Peace,” we see the artist’s humanitarian vision, linking the past and future. People around the world come together in positivity and harmony while honoring one another’s traditions, heritage, and individuality. We see Thiago’s personal perspective as an autistic artist, depicting acceptance for people of all abilities.

“Journey Through the World” 2020, mixed media on Canson paper, 17×11 in.

This drawing shows five balloons representing five continents of the world: Asia, Africa, America, Europe, and Oceania. Each balloon displays flags of countries within that continent. Thiago depicts himself riding in the baskets of all the balloons, dressed in traditional clothing from locations on each continent.

“Sasithorn Yomyiom” 2021, mixed media on Canson paper, 17×11 in.

Sasithorn Yomyiom is the name Thiago gave to the Thai martial artist in this drawing. The name “Sasithorn” is of Thai origin, meaning “the moon” or “from the moon.” Thiago shows her in the Buddhist palaces of Bangkok, under a full moon.

“Cyrille Henri” 2021, mixed media on Canson paper, 17×11 in.

Cyrille Henri is a French-Guyanese Le Djokan (Le Djokan is a martial art from French Guiana). He is standing in the streets of Cayenne, the capital of French Guiana. Above his head, within the cityscape, is the symbol of Le Djokan on a fighters’ organization building. The official French tricolor flag flies in the background, behind the locally used flag, a diagonal bi-color of yellow and green with red star.

“Leggero Protettore” 2021, mixed media on Canson paper, 17×11 in.

“Leggero Protettore” in Italian, translates to “Light Protector.” The subject is a Vatican Soldier, a Swiss Guard of Italian descent. He is shown standing in front of St. Peter’s Basilica, in Vatican City.

“Cowboys e Cangaceiros” 2021, mixed media on Canson paper, 24×17 in.

In this complex drawing, a mysterious alien invasion takes place in both the US state of Texas and the hinterlands of Pernambuco, Brazil. The artist uses a center line, which creates a mirrored composition to great effect. The alien is rendered in counterchange, suggesting a dual nature. The horizon line shared by both locales reinforces the simultaneity of this conflict, and the placement of the title figures invites comparisons and contrasts between each side of the drawing.

On the left, we see the Cowboys: “Tyce McCarty” from Texas, behind him, Cowgirl “Wendy,” and Native Americans “Mayara” and “Comanche,” protectors of Austin, Texas. On the right, the Cangaceiros: “Renato Ferreira” from the backlands of Pernambuco, and behind him, the protectors of Pernambuco’s hinterland ”Renata Nunes” (a bandit), “Miguel Ferreir,” (a water seller), and a Chihuahua named “Speed.” The hinterland, or backland, is a dry and rugged inland region of Pernambuco. Cowboys in the US and Cangaceiros in Brazil are part of the history of their respective countries. They are also iconic genres of literature and film, and the artist includes a movie poster-style banner at the bottom of the drawing.

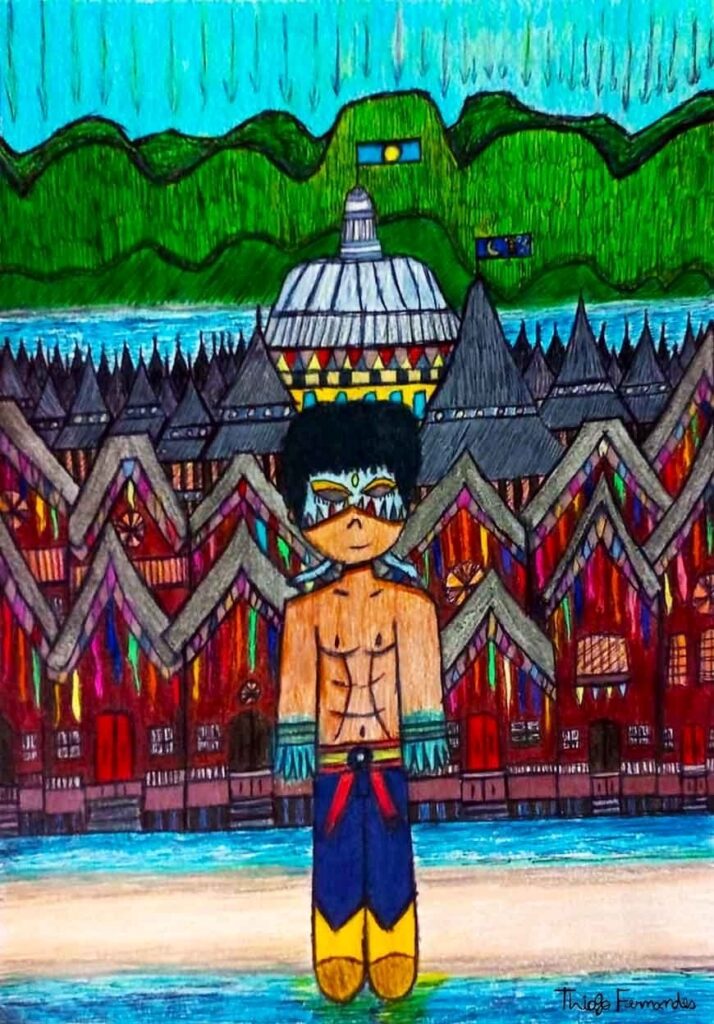

”Haruo” 2021, mixed media on Canson paper, 17×11 inches.

The subject, Haruo, is a Palauan fighter, standing in front of traditional Palauan houses with decorated gables. Above Haruo, the domed building flying the flag of Palau is the capitol building located in Melekeok, on a site called Ngerulmud. To its right, an adjacent building flies the flag of Koror, home of Koror City, Palau’s former capital. The artist alternates planes of land and water against deep green hills, to depict this nation of islands.

“Lueji Luanda” 2021, mixed media on Canson paper, 17×11 in.

The subject of this drawing is an Angolan Bassula martial artist. The cityscape behind her is Luanda, the capital of Angola. Above her to the right is the Angolan flag atop the National Assembly building.

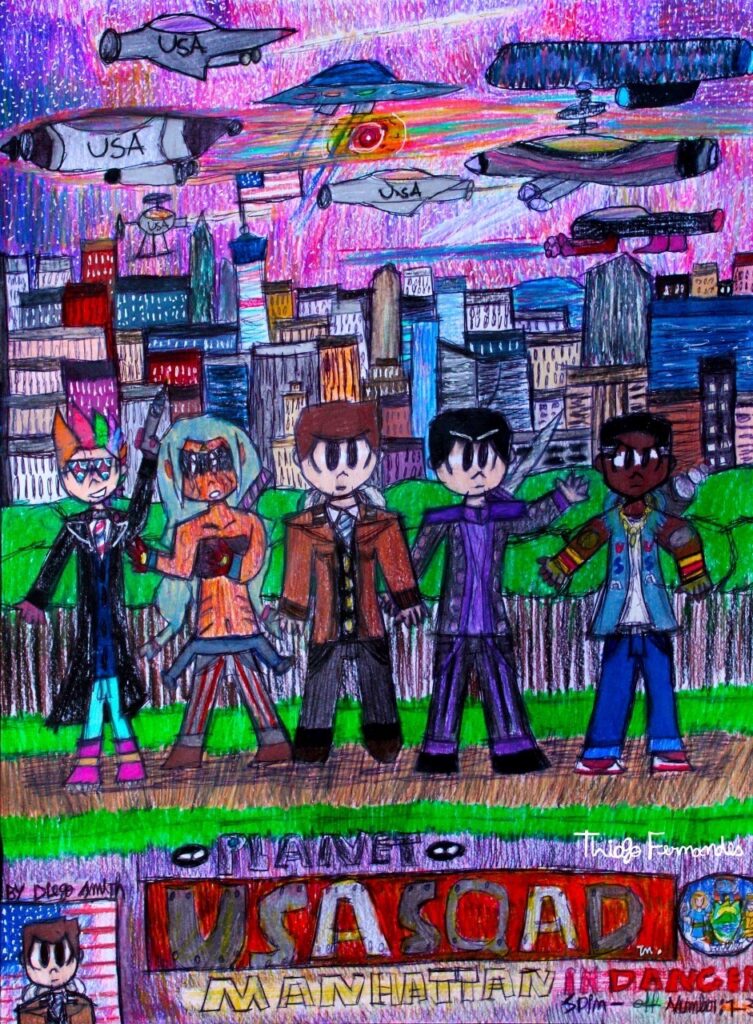

“USA Squad Manhattan in Danger” 2021, mixed media on Canson paper, 17×11 in.

This drawing depicts an invasion of various aliens in Manhattan. The narrative summation of its subject and title text block at the bottom creatively employs movie poster style. Three American characters, a British man, and an alien from an unknown planet are shown prepared to battle with the enemies in the borough’s parks. On the left is the New York punk Loyd Vicious and the alien Ahsuki Tarano, in the middle is the New Yorker Diego Smith, and on the right are Englishman Christopher King and Sire Tureaud. In the center of the sky, a negative energy is opening, where ships of United States space organizations are attacking the ships of different extraterrestrial peoples.

“World Peace” 2021, mixed media on Canson paper, 17×11 in.

The artist shows himself in the center foreground, in his spaceship accompanied by ten unique characters from different nations. Behind him, English soldier “Christopher King,” Russian soldier “Rushell,” and “Frenk Lenis,” a French detective. In the front row, from left to right: Brazilian musician “Rodrigo,” in green, “Hwi Kumiko” a Chinese Kung-Fu fighter, the artist, in white, “Moisés,” an Egyptian spiritual guide, Diego Smith, an American fighter in New York, “Wesley Sydney,” an Australian veterinarian, “Akim,” a South African warrior, and “Amiria,” a New Zealand Maori witch. They are together to promote peace in the world.

“There Is Hope” 2021, mixed media on Canson paper, 17×11 in.

This composition is solely focused on people from different countries, ages, races, beliefs, and abilities: a worldwide diversity. Each individual is shown releasing a light that comes from within them. This light symbolizes positive energies, collectively released in an effort to defeat the bad thoughts and feelings – or negative energies – existing in the world. The artist depicts these negative energies as multicolored vibrations in the sky.

For more information about Thiago Fernandes including how to contact the artist, please contact Veronica Federiconi at 716-713-2734 or email federiconiveronica@gmail.com

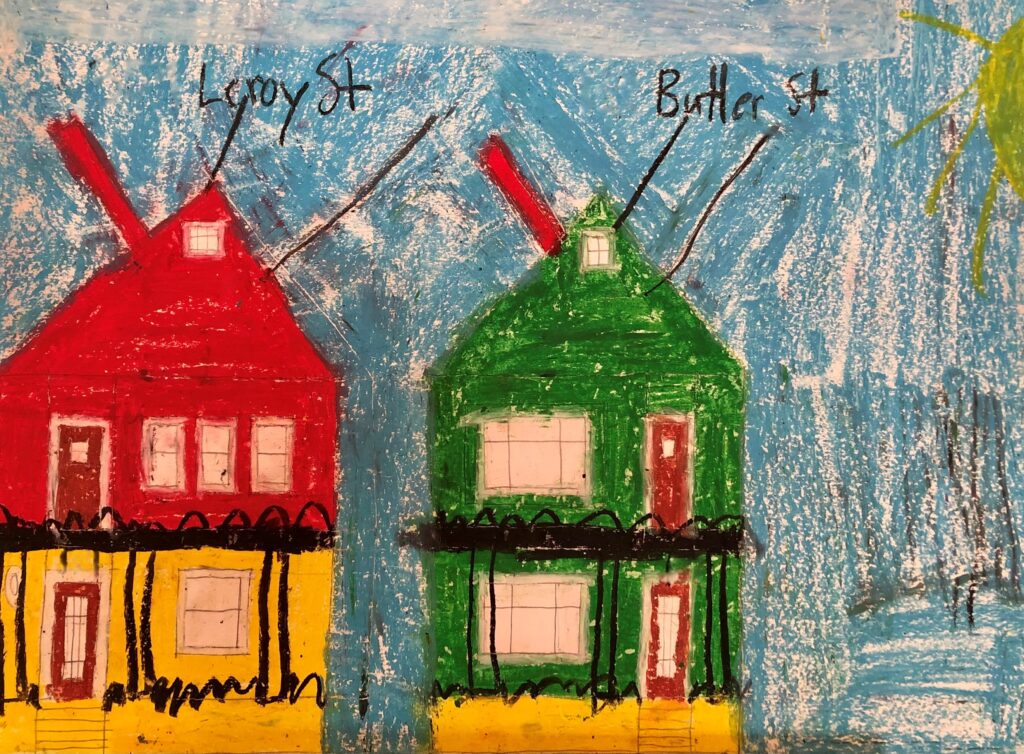

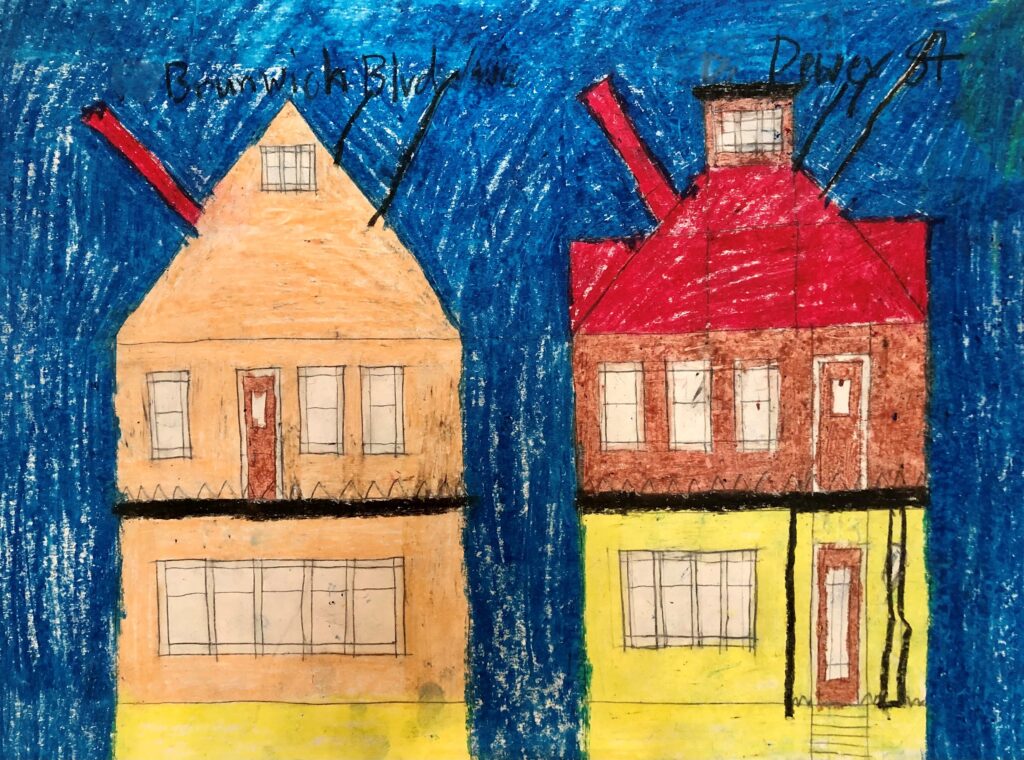

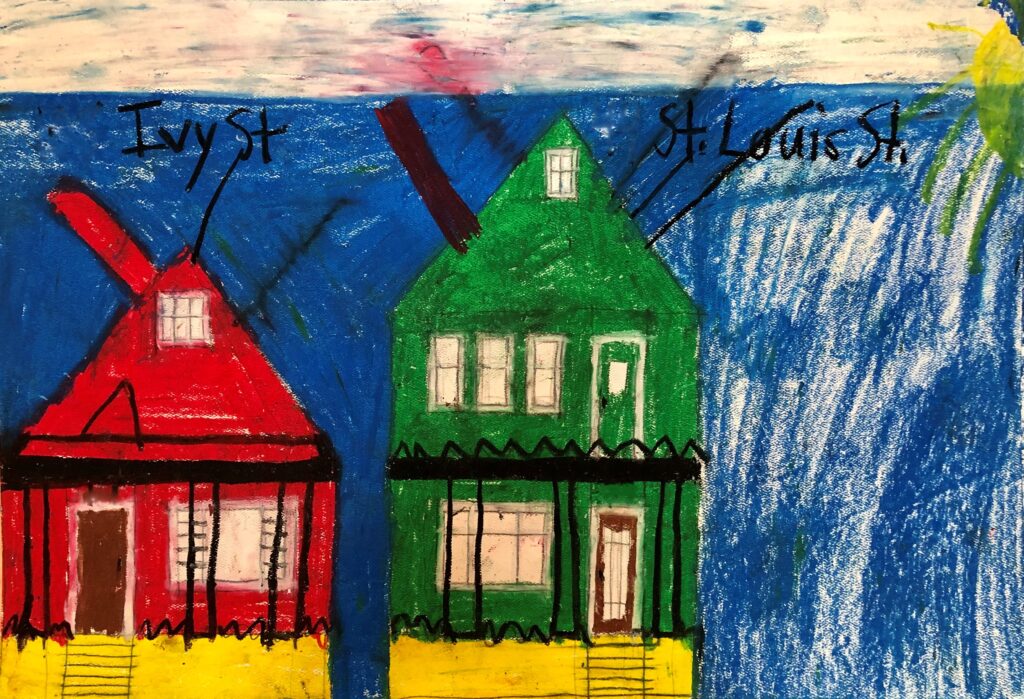

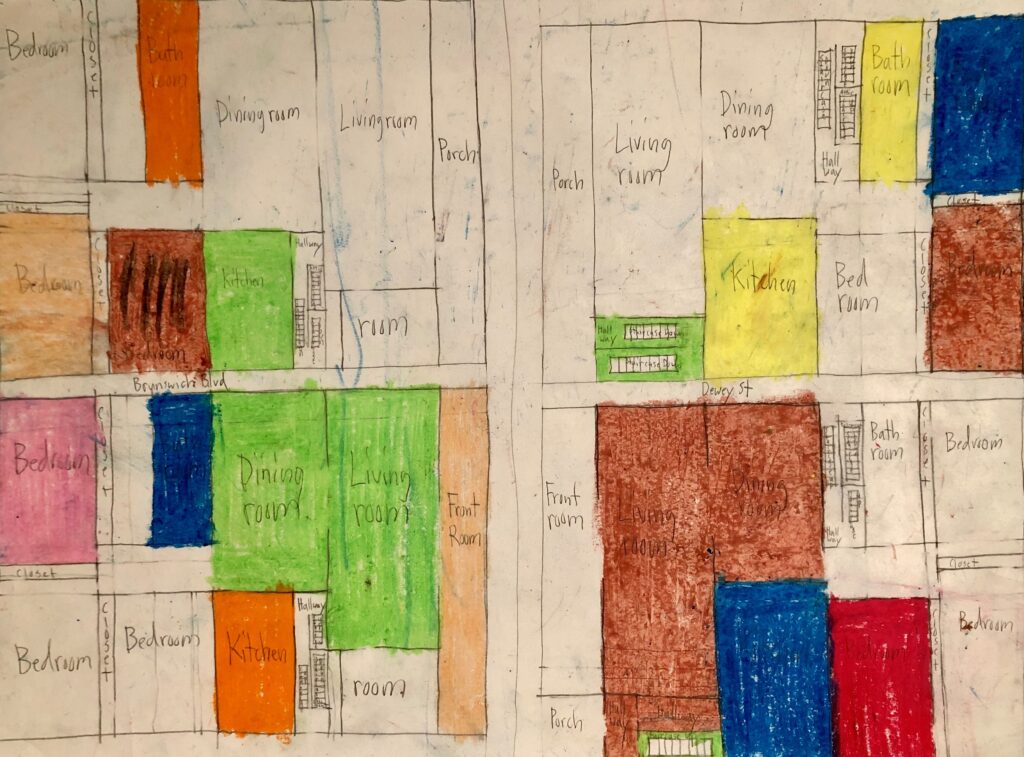

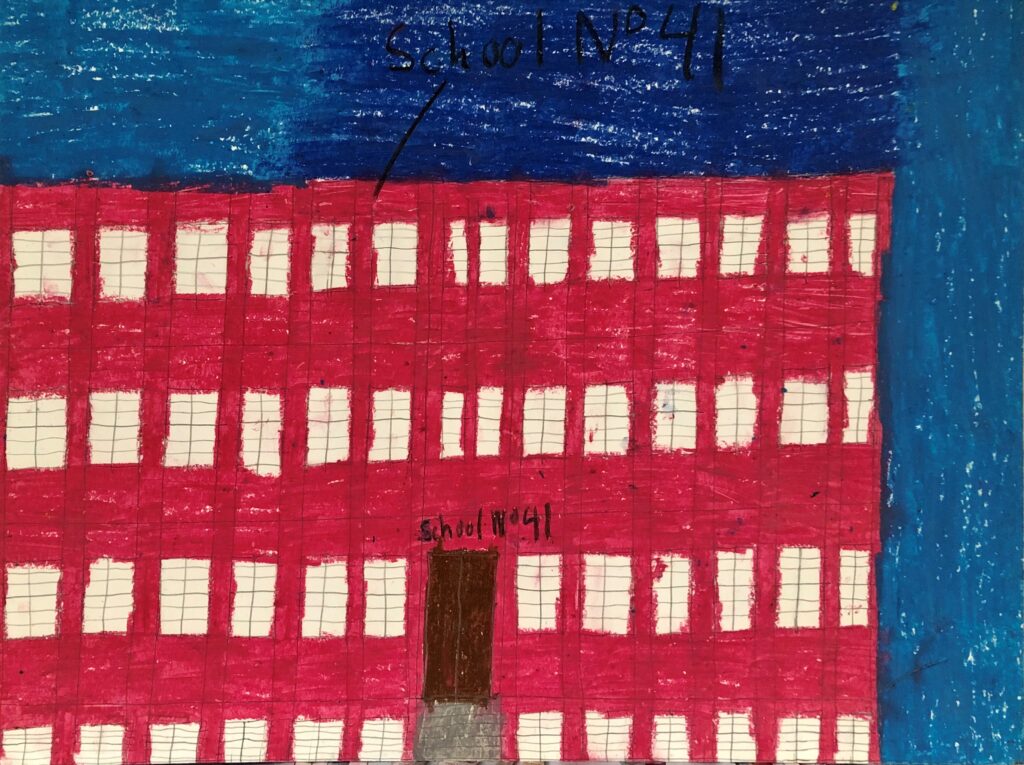

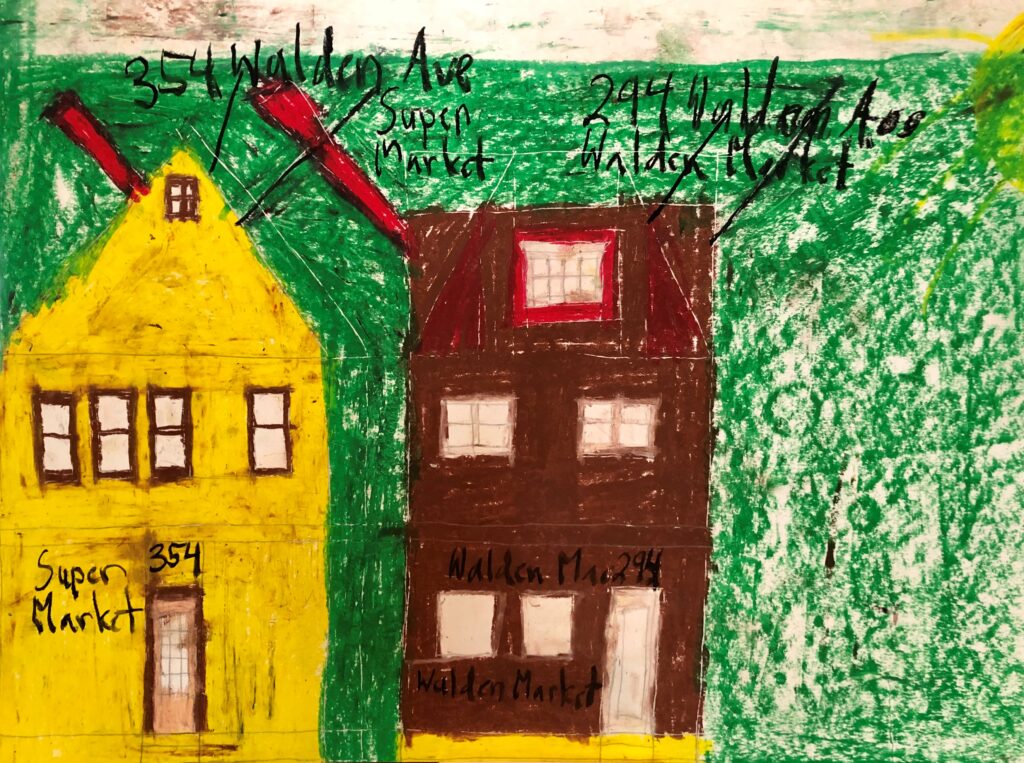

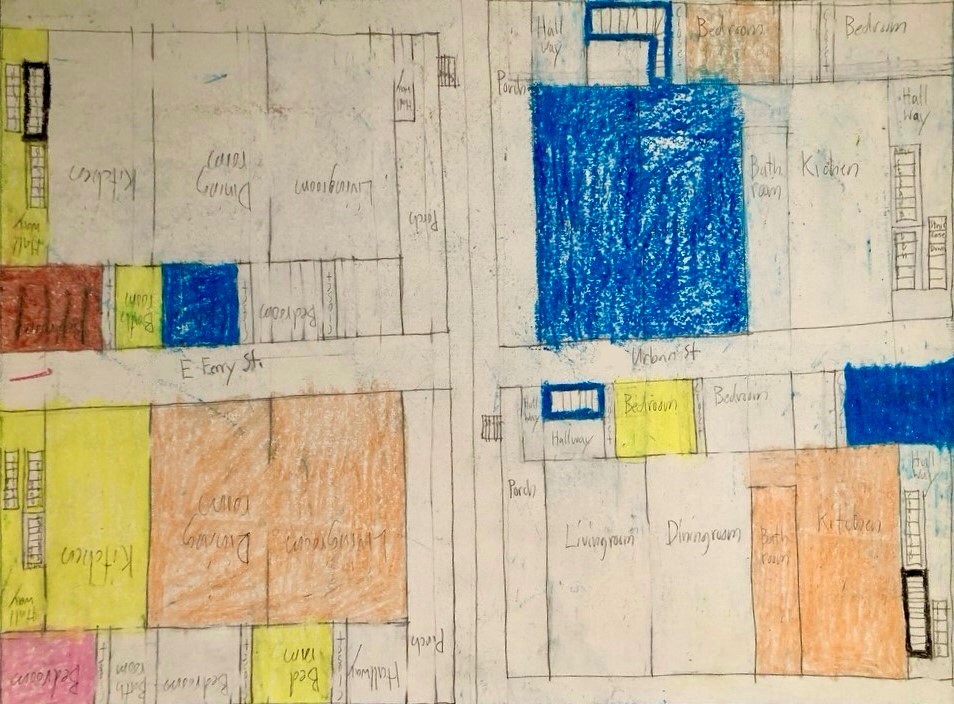

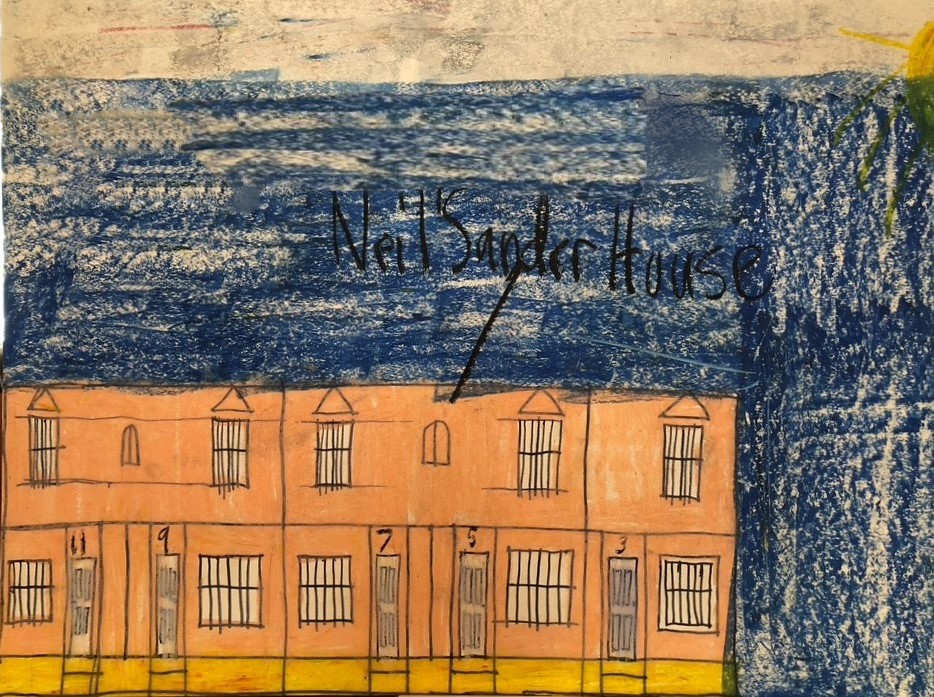

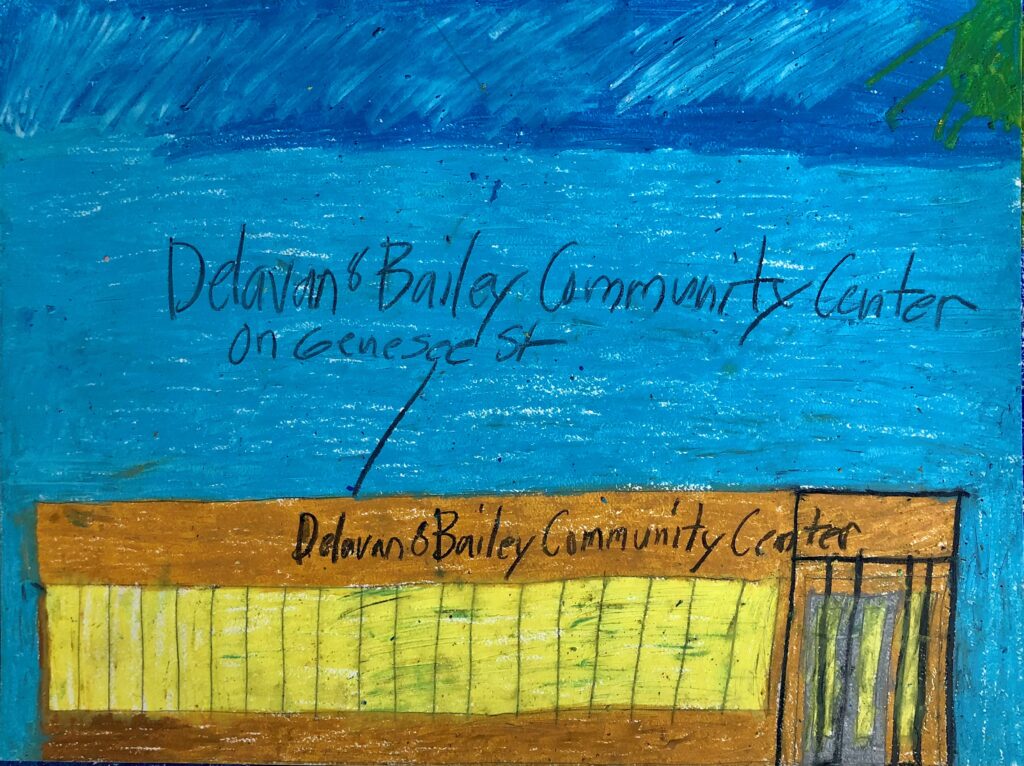

Aaron Brown: Where I’m From

“Aaron Brown creates accurate drawings of buildings from memory, in pencil, oil pastel, and marker. He does not use reference materials. It is as if his eyes have taken a photograph and his mind stores it and relays the information to his hand as he draws. When Aaron draws, he is reminiscing. His drawings are postcards from his memory.” ~Teaching Artist Todd Lesmeister

Where I’m From: Aaron Brown’s Hometown Anthem By Ahmad Jordan

Rap music was my introduction to Aaron. Yes, rap music. Sure, I had seen Aaron around at Autism Services before, walking through the hallways with his headphones on, and I had even seen him perform with the band No Words Spoken. But true to the band’s name, Aaron is a no-words-spoken kind of guy. I’d say hi, he’d say hi back and he’d keep on steppin’. It never felt rude, mostly because Aaron always moves around in a good mood. You get the sense that there’s a conversation going on in his head and, if anything, I’m the one who is being rude for interrupting. So my association with Aaron was always in passing. But there was one exception.

I was recording a podcast with Neil Sanders, a mutual friend of Aaron’s and mine. Neil is autistic and, like Aaron, there’s a screen in his head that he’s always tuned into. But Neil doesn’t mind so much unplugging to entertain me—and Neil is nothing if not entertaining. He has his own radio-style brand of gossip and, like calling in on a radio show, we are all welcome to interrupt. In fact, Neil’s podcast is pretty much a radio show. I was a sort of de facto producer and occasionally, the caterer. So one day, after wrapping up our recording, I grabbed my keys to take Neil to Burger King.

On the way to the car, I looked behind me and there was Aaron, semi-smiling.

“Hey, Aaron.”

“Hiiii.”

Aaron stretches his vowels, and because of his deep baritone, his words make a slow-motion moan. Right away I could see what was going on here. He wanted in on the Burger King action. Cool. Hop aboard, my man. He took the back seat and Neil rode shotgun.

I closed the door and the acoustics of the car allowed me to hear what was playing through Aaron’s headphones. It was faint but familiar.

“What are you listening to, Aaron?”

“Busta Rhyyymes,” he answered, stretching out that Y.

I’m not sure why I was surprised. Maybe I was just excited to learn that Aaron and I shared the same taste in music and music artists. As I learned from Aaron’s brother Jon, “Aaron listens to mostly rap. Some R&B. Back when cassette tapes were in, he’d make his own mix tapes from WBLK. He would also listen to some of the music I had recorded while I was in New York City. Back then it would take a while for music from New York City to make it to Buffalo, so people in Buffalo never knew who these acts were yet. So I’d make dubs of music being released by New York City artists: Wu-Tang, Fat Joe, Lords of the Underground.” All of this means that Aaron probably knew about Busta Rhymes before I or the rest of Buffalo did.

I waited and listened closely to the music pulsating in Aaron’s earphones. I knew the keyboard melody. I knew the song. “Been Through The Storm” featuring Stevie Wonder. It’s a hometown anthem about growing up in Brooklyn. I’ve never seen Brooklyn, but if you’ve been through the storm, any storm, then in a way, you have. America’s ghettos are a template, they are spread throughout the country and the people who live in them are connected by shared experiences, enough so, that a Buffalonian like myself can press play on “Been Through the Storm” and within five minutes I feel connected to Brooklyn. I can relate. But here in the back seat of my car was Aaron, going through the storm with Busta Rhymes. Aaron is African-American. Aaron is autistic. Aaron is part of this shared experience.

Aaron doesn’t talk about his place in the African-American experience. Remember, no words spoken. But that doesn’t mean that he’s not expressing it. With his band No Words Spoken, music functions as his universal language—but not his only language. Visual arts have given Aaron a bi-lingual advantage, allowing him to show, if not tell, what catches his eye and what’s important to him. This is true of all artists. We go to a gallery and chances are, the artists are not present to speak for themselves, so the art stands in their stead as emissaries. The same is true for the autistic, for Aaron. There’s a theme that ties Aaron’s art together, one that is reminiscent of the signature hometown anthem that so often appears in rap music.

A phone call to Aaron’s mom had her digging through Aaron’s archive of artwork. The first drawing Mrs. Brown pulled out was of School 31, otherwise known as Harriet Ross Tubman School. Aaron chose to illustrate a school named after America’s most famous Freedom Fighter. If anyone has been through the storm, it’s Harriet Tubman. Makes me wonder if Aaron’s listening to Kodak Black’s epic song “Harriet Tubman.” Who knows, but after speaking with Mrs. Brown, it is clear that this is no one-off. Aaron has been documenting his environment since the age of five.

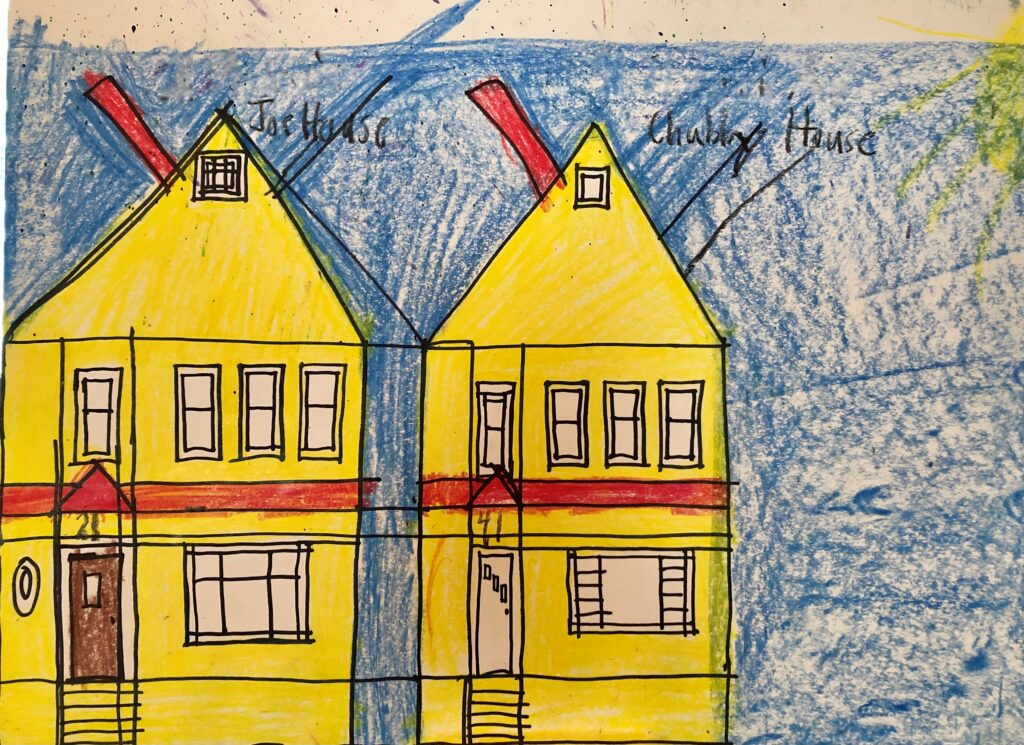

“He started with Lego buildings,” Mrs. Brown said. “He had paint buckets full of Legos. We set up a picnic table in the kitchen and he would spend hours constructing entire buildings and sometimes cities. He started doing this at five.” And he never stopped. Eventually he put away the Legos, picked up a pencil, and started drawing, mostly buildings and cities. “He wasn’t using crayon or marker,” Mrs. Brown continued. “Just pencil. He started drawing everything. He would only need to see it once and then he’d come home and draw it.” Jon adds to this: “I always just thought he has a photographic memory. His drawings are always exact: the number of windows, the general shape of the house or building and where the doors and windows are supposed to be; he’d remember these things and they’d show up in the right place in his drawings. And he’d remember who lived there too! I couldn’t even tell you who lived where, but Aaron always remembers. He’d point at a drawing and say, for instance, ‘Joe’s old house.’” Who is Joe, I wondered, certain that it would be someone close to Aaron, like a family member, but no. “Joe was just my brother’s friend,” Jon said.

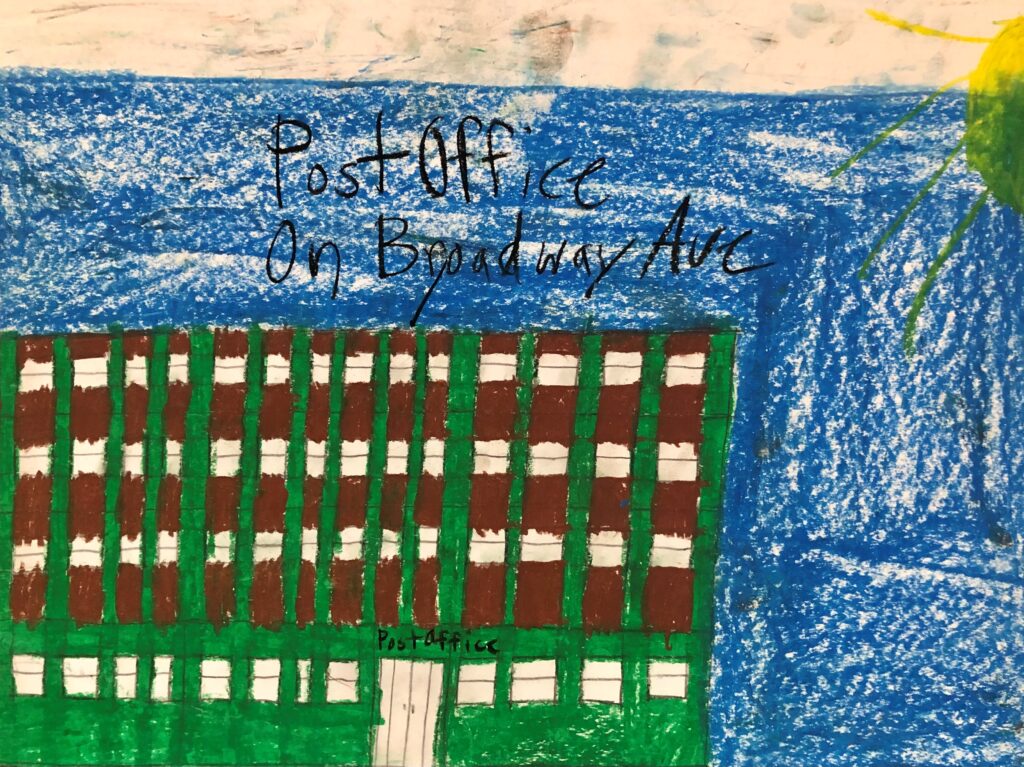

Mrs. Brown has saved most of Aaron’s work. Even on the phone she was paging through reams of it, and if there’s one word that sums up Aaron’s fixation, it’s this: environment. He has something to say about the environment he grew up in and the environments he’s experienced.

Aaron comes from a broad-minded family. Though they have lived in the same house for thirty-five years, they aren’t afraid to spread their wings and fly beyond their immediate environment, taking Aaron and his two older brothers with them. Aaron has been to New York City. He has seen the Empire State Building. Most people will not miss an opportunity to photograph the Empire State Building, just so that they can say that they’ve been there, but that is not the case for Aaron. When he got home he eschewed the famous 100+-story Art Deco monument in favor of New York’s once infamous sprawling subway system. That’s what Aaron drew.

There’s another Busta Rhymes song called “New York.” It has a seesawing horn sample that takes you straight to 1970s Broadway. Busta Rhymes, being the gifted lyricist that he is, goes into a rhyming roll call of all things distinctly New York; one of them, of course, is the subway system.

Subways are moving snapshots of the environments they pass through. In Buffalo, our subway pragmatically runs in a straight line, passing through and threading the city’s wanton segregation. At any given moment, for better and for worse, every demographic is in the same enclosed environment. As a kid I remember the tension this created as it underscored America’s racial division. I also remember how it unified a divided demographic, even if unwittingly. I’d meet people on the subway, people who didn’t live in my neck of the woods, and I didn’t live in theirs. For ten minutes or so, maybe longer, I’d share space and time with a person I wasn’t likely to meet in any other environment. This is true of every subway system. So what does it mean that Aaron seized the subway and not the Empire State Building as his subject?

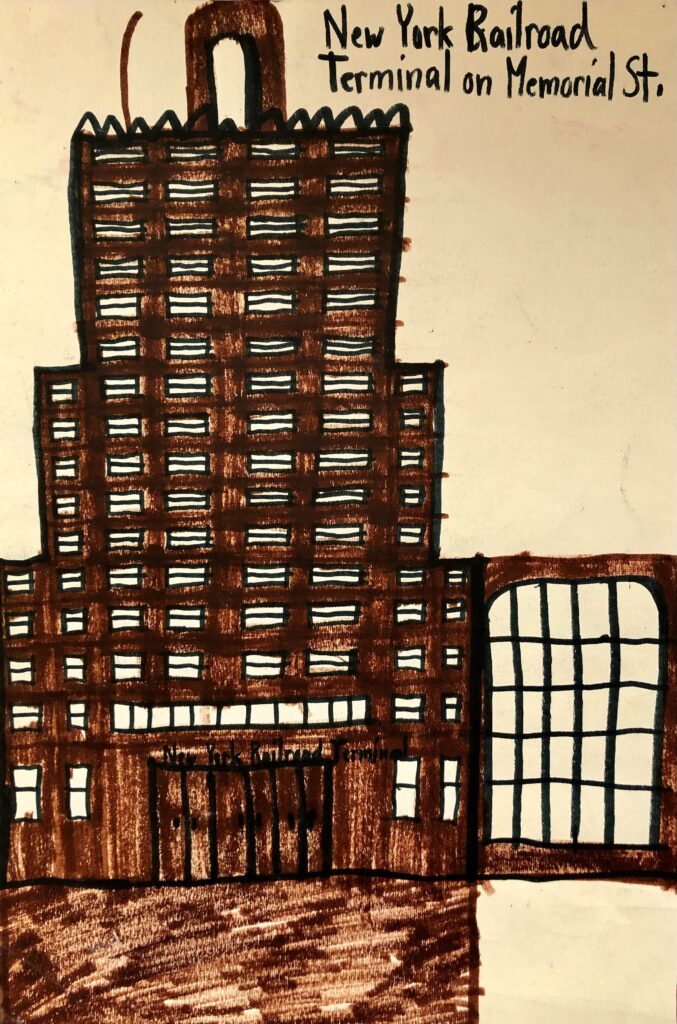

At the very least it means that Aaron is selective. He’s making editorial choices, and this is not the only time that Aaron has made such a decision. “He did a drawing of the Central Terminal,” Mrs. Brown told me. My eyebrows must have risen. Everybody knows the Central Terminal. It’s Buffalo’s shared experience. It’s an icon of the city. I will even venture to say it is a symbol of the city. At one time it was just like New York City’s subway system. It teemed with people of every walk of life; it bustled, until it didn’t anymore. It died and fell silent, but it is still there and you can feel a latent resurrection baked into its bricks. It wants to thrive again. Just like Buffalo.

Environments aren’t neutral; they’re alive with people; they age with us and, like people, they decay and die. Knowing this relationship between people and environments, Aaron writes the names of the people who are attached in one way or another to the places he illustrates. Remember Joe, the friend of Aaron’s oldest brother? His name is scrawled across one of Aaron’s drawings. There’s also Venice, Nancy, Anthony, another Joe, and Liz, who is one of Aaron’s friends at Autism Services. Then it gets real personal: Aunt Carol, Aunt Birtha and Aunt Onell. One name in particular jumps out at me: Neil.

Many of the homes and buildings that Aaron drew of his neighborhood are no longer there. As Aaron’s mom explained, “When we first moved in the area, Aaron was eight years old. The neighborhood was filled with mostly homeowners. But then it changed. People moved out. The houses were abandoned. The city claimed the property and eventually it was all demolished. It’s all just plain fields now. Many of the houses that Aaron drew since he was a kid aren’t there anymore.” She was talking about 21, 38, 41, and 48 St. Louis Street—all homes that Aaron drew and every one of them now gone. Empty fields are all that remains.

Jon’s additions to this observation are especially poignant. He left home to live in Columbus, Ohio, and stayed away for a good fourteen years. He’d come back intermittently; with each return he saw how Buffalo was changing. “Each time I returned home, houses would be boarded up or just gone. Some parts of Buffalo started to look like war zones. Half the houses are now gone; there’s just empty lots now.”

Houses once stood there and people once lived in them. Surely, the memory of these homes survives as photographs, probably old 4 x 4 Polaroids. But they survive in Aaron’s drawings too.

Which brings me to the obvious observation about Aaron’s style. His illustrations today are as sincerely rendered as when he was a five-year-old boy. Buildings and homes are reduced to simple shapes and flat colors, nothing more. Anyone who thinks that Aaron’s work is “child-like” is to be forgiven, but they should also understand how his youthful flair frames the poignant passing of time; Aaron gives us one half of the before-and-after dualism, showing us through contrast just how much environments age. For buildings and homes that have visibly exceeded their life expectancy, Aaron’s renderings function as their baby photos. His bold and bright colors remind us of what these lived-in spaces had once been when they were born.

As my conversation with Aaron’s mom concluded, I couldn’t help but to see so many parallels between our families and our environments. We did not grow up on the same street, but my childhood neighborhood was only a two-minute drive away from Aaron’s. Every picture Aaron has painted of the Genesee-Walden area is like a photograph of my own memory growing up on Leslie Street, just off Genesee. I know the homes. They are two-story and spacious. The people who lived in those homes owned them. But those people drifted away; death took them or they simply moved on. It’s the one thing that environments don’t have in common with people. Environments stay put. Their mutations happen over time but in the same space. The people who move in and out become an animated palette, allowing us to see the canvas as it slowly shapes and shifts. I know the colors of my community. I know the music. I know the people. I am the people. So is Aaron. This is our shared experience.

Before I started the car engine, I pressed my ears against the air to hear Stevie Wonder providing the chorus for “Been Through the Storm.” The song ends so cinematically that you can easily forget it’s a rap song. By the time it did end, I forgot that we were supposed to be on our way to Burger King. Neil reminded me.

“Um…” Neil always begins an interjection with um or with actually. “We WILL be on our way to Burger King in… I’m going to say…” He paused to look at his wristwatch. “By 1:03pm.” The time on my dashboard was 1:02. That was Neil’s way of saying what are we waiting for?

This all happened years ago. Everything I just wrote down is all from memory, which tells you how memorable the autistic experience can be.

“Okay, Neil,” I said, taking the hint. I started the car and pulled off. I looked in the rear-view mirror at Aaron and he was back in his own world. I told Mrs. Brown about this episode and she laughed. But she made a salient point. “Just because he’s listening to his headphones doesn’t mean he isn’t listening to you. That’s how the autistic brain works. It can do more than one or two things at once.”

She’s right. I fished into my CD stash, found Busta Rhymes’ album (I’m a fan too, y’know) and popped it into the player. I was determined to reconnect with Aaron. We were both fans of Busta and I didn’t want to let that go. I pressed play and waited. Aaron never removed his headphones. I was disappointed. But then something happened: Busta said a cuss word—a nasty one. Neil immediately pounced on it, practically pointing an incriminating finger at the speaker. Busta Rhymes was busted! Whatever Neil said about Busta’s bad mouth, unfortunately, my neuro-typical brain can’t recall, but I can tell you that it was hilarious. And I wasn’t alone in my outburst. I looked again in the rear-view mirror and Aaron’s semi-smile had broken into an all-out laughter. For that brief moment three African-American men, one neurotypical and two autistics, had a shared experience. Three brothas. Not brothers—brothas.

For the record, the Busta Rhymes scandal was my fault. I know the lyrics and should have known better. I hit eject and the rest of the ride was pretty much a quiet one. Neil tuned me out and tuned into his headphones. As for Aaron, he had already returned to his own neighborhood, the one in his head. Subways. Central Terminals. Old neighborhoods and old homes. The trick here, of course, is to avoid putting words in Aaron’s mouth. However, by its very definition, art is subjective; it’s open to interpretation, so it’s fair game for me to wonder if Aaron is doing the same thing Busta Rhymes did with “New York” and “Been Through The Storm.” Aaron is making a shout-out to Buffalo, his hood and, more saliently, his world. Aaron’s architecture, I believe, is a hometown anthem. He’s celebrating where he’s been and where he’s from.

Aaron Brown’s Buffalo Schools: Postcards from Memory is on view at WNED/PBS Horizon’s Gallery wned.org/horizons

For more information on Aaron Brown and his work please contact arts@autism-services-inc.org

Aaron Bro